Contrary to what you might have thought, hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking” is not a practice exclusive to the 21st century. USGS has records and data collected all the way back from 1947, used to help determine the environmental impact over the last 63 years.

What is fracking, and why should you care? First of all, hydrofracturing is not a natural occurrence, and that alone should be a reason for you to care. If humans are unnaturally using water, chemicals, and abrasives, to crack open deep rock beds, you should be asking yourself what impact there is on more than the immediate environment.

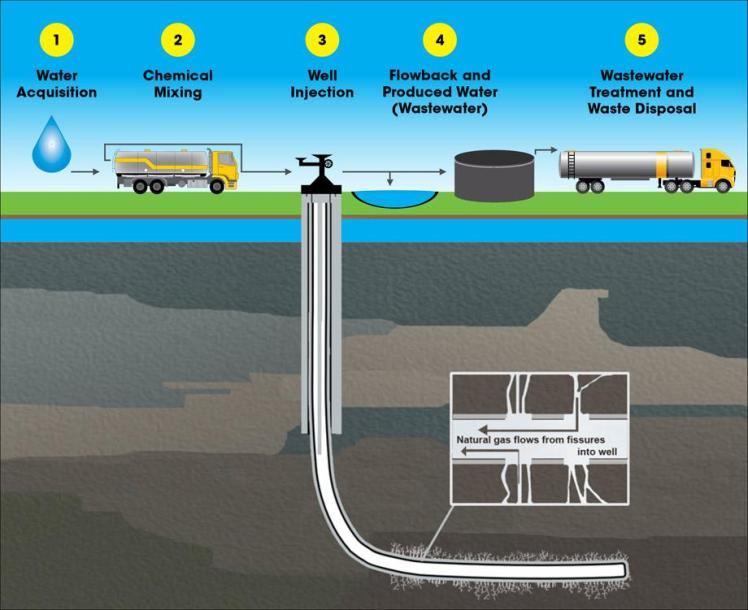

Hydraulic fracturing,to put it simply, extracts oil, gas, and petroleum that is trapped in rocks through wells drilled using water, , chemicals, sand, and other proppants (materials used to keep fractures open, includes solid materials, sand, treated sand, or man-made ceramics). Once the well is drilled, metal pipes are inserted for extraction of gas, oil, and petroleum. There are two types of gas oil companies are drilling for: conventional and unconventional. Conventional is simply oil and gas, whereas unconventional includes shale gas, tight gas, and coal bed methane.

There are more than a few problems with fracking, beyond the geological impact (can we say earthquakes in the midwest? Google search a map of the tectonic plates and you’ll see what I mean). It’s not a coincidence minor seismic activity is more prevalent in areas known for hydrofracturing, but we won’t get into that just yet. For most Californians, like myself, the idea of the sheer volume of water used each year is enough to send me into convulsions. It is estimated that 70-140 billion (yes, that’s with a b) gallons of water are used for the 35,000 wells across the country every year. And to transport all that water? It takes about 1,400 trips to move 2-5 million gallons, which equals about 39,200,000 truck trips each year. It’s unlikely Priuses are being used to haul all this water.

Almost as concerning as the amount of water used is the chemical component of extraction. Though only about .5-2% of chemicals are used in the total volume of fracturing liquid, this does not mean the levels of chemical contaminates are safe. Even small quantities can contaminate millions of gallons. To see the list of chemicals used, you can visit earthworksanction.org (it also goes into a lot more detail than this post, if you fancy it). Some include kerosene and diesel fuel, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, methanol, formaldehyde, ethylene glycol, glycol ethers, hydrochloric acid, and sodium hydroxide. Most of the chemicals used are not only toxic, but also carcinogenic and dangerous for humans and wildlife.

Also used are volatile organic compounds (or VOCs). These can easily get into the air, especially if pools of water containing VOCs are left standing. This means the water, surrounding soil, and air are now contaminated. A water source in Texas was sampled and results showed 1,2-Dichloroethane had contaminated the water at 1,580 ppb (parts per billion), roughly 316 times the EPA’s maximum contaminate levels for that particular VOC.

What happens once the fracking water is no longer used for that particular location? The waste material is either reused or disposed of, creating yet another environmental concern.

Keep in mind, it is advised non-toxic methods be used, so it is possible to fracture without the necessity to use chemicals. One of the biggest problems with chemical hydraulic fracturing is the vulnerability of local water sources. Some coal beds are pure enough to be labelled as underground sources of drinking water (USDWs), but a 2004 EPA study found even these are being contaminated.

There has been a lot of push in the media lately for mining of natural gas and keeping sources of said natural gas within our own borders. But at what cost? At some point we need to consider what truly defines “clean energy” – if that means contaminating local water sources, endangering humans and wildlife, and wasting billions of gallons of water and compromising natural sources of drinking water, then hydraulic fracturing is the answer to our energy question. I understand our modern world runs because of these natural sources, but is it worth all the outcomes we’re given as a result?

Venture on and question everything, my dear readers.

*For your reading and reference pleasure, go to: energy.usgs.gov and earthworksanction.org